On October 29 2023, a 45-year-old American named Joshua Farinella flew into the city of Amalapuram near India’s eastern coast to start his new job as the general manager at a shrimp processing plant owned by a company called Choice Canning. Farinella, who is softly spoken with a shaved head, neatly trimmed beard and full sleeve of tattoos, was excited about the prospect of living abroad for the first time.

True, this would be a high-pressure job, and he would miss Christa, his wife, but he had negotiated a salary of $300,000 a year, more than double what he’d earned at another seafood company in the United States. He joked that he was now the best paid shrimp worker who did not own his own company. He figured that if he could stick it out for two or three years he would be set up for life: he looked forward to upgrading his camper van, paying off his car loan and setting aside some money for his stepdaughter’s university education.

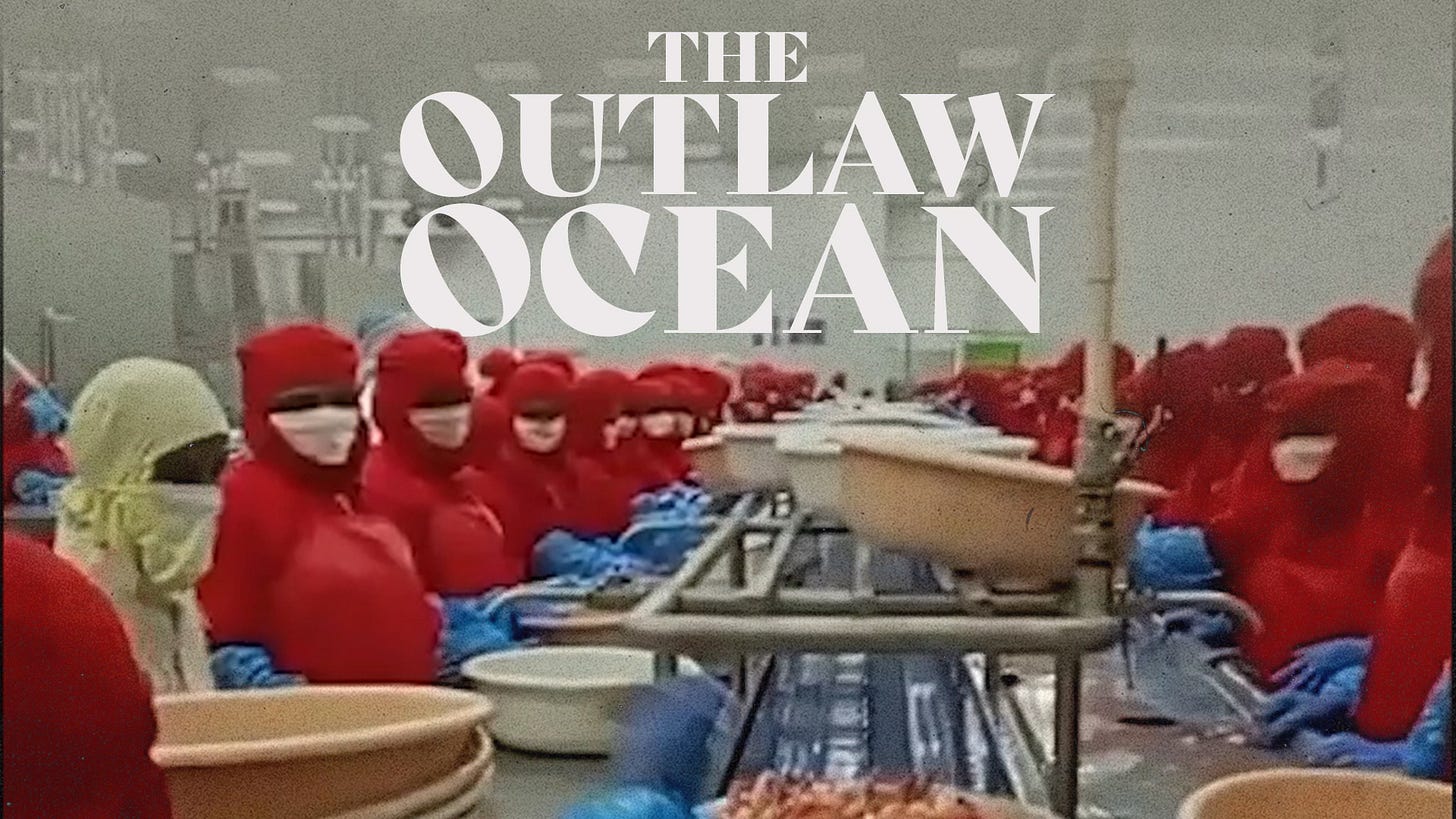

Farinella’s dream quickly turned into a nightmare. He soon discovered that the plant’s largely female employees were effectively trapped on the compound, routinely underpaid, and forced to live in inhumane, unsanitary conditions. The managers were also misleading auditors and processing shrimp with banned antibiotics. It soon dawned on him that he’d been hired as an American face to “whitewash” a forced-labor factory. Over several months, Farinella meticulously gathered evidence that he brought to the Outlaw Ocean team. The results of that investigation are the subject of the fifth episode of the Outlaw Ocean Podcast, Season 2. The podcast is available on all major streaming platforms. For transcripts, background reporting, and bonus content, visit the Outlaw Ocean Podcast, Season Two. New episodes are released weekly.

In recent years, India has exploded as the dominant source of shrimp for much of the world, with support from its government through subsidies and loosened foreign investment restrictions. In 2021, India exported more than $5 billion of shrimp globally and was responsible for nearly a quarter of the world’s shrimp exports. Choice Canning is one of the largest Indian suppliers in the market, with corporate offices in two big Indian cities, Kochi and Chennai, as well as in Jersey City, N.J.

Choice Canning categorically denied Farinella’s claims and said that the company never underpaid workers, prevented them from leaving without permission, or maintained subpar living conditions.

On any given day, there might be more than 650 workers at the plant, typically hired by third-party contractors. Hundreds of the workers lived locally in Andhra Pradesh and went home at the end of each day. The rest were migrant workers recruited from impoverished corners of the country who lived at the plant. A security guard was usually posted outside near the building’s front door. Soon, Farinella found migrant workers living on the compound in deplorable conditions — like shared beds with bedbug-infested mattresses — as well as downright dangerous conditions, like a secret dorm above the plants’ ammonia compressors. He also realized there are hundreds more people living on site than the paperwork accounts for, and they cannot freely leave.

At 3 a.m. on November 11, 2023, a manager sent Farinella a WhatsApp message informing him that a woman had been found running through the plant’s water treatment facility. “She was searching for a way out of here,” the manager wrote. “Her contractor is not allowing her to go home.” The woman made it as far as the main gate but was turned back by guards.

Forbidding workers to leave their plants when they choose to is a violation of the Indian constitution and also likely violates the country’s penal code, according to the Corporate Accountability Lab, an advocacy and research group. When Farinella arrived at the plant several hours later, he tried to get an answer about what had been going on—and was told by an HR manager that it had all been a misunderstanding. The woman had not wanted to leave after all. An alarm bell went off in Farinella’s mind.

On January 3, 2024, news outlets in India reported that a group of about 70 workers, many of them women, marched to a police station in the Andhra Pradesh province to demand that action be taken against a labor contractor at their workplace, the nearby Choice Canning shrimp factory.

The workers alleged that the plant’s labor contractor stole approximately $2,600 in wages, equivalent to about two years of an average worker's salary. They also demanded a manager be charged for abusive language under Indian legislation that seeks to prevent hate crimes against members of underprivileged castes - many of the workers were from India’s lowest caste, called Dalits or “untouchables.” Local media reported Choice Canning had properly paid the contractor, who then withheld payment. Following police intervention, the contractor repaid roughly $1,600 to the group.

Farinella was concerned when he found workers sleeping on the floor, but he said he and others struggled to get authorization for the necessary changes. A few weeks later he discovered during a recorded conversation with two labor contractors for Choice Canning that 150 workers had not had a day off in a year. It was also hard, he said, to tell how long employees spent working. A human-resources executive admitted candidly in a Zoom meeting recorded by Farinella how she would need to adjust attendance records and timecards for an audit.

Processing seafood is a race against the clock to prevent spoilage, so the Choice Canning plant in Amalapuram runs more or less 24/7. There’s also not a lot of automation in shrimp processing, so this means that the factory relies on an enormous amount of labour to deliver 40 shipping containers full of packaged shrimp — every single day.

The story about conditions at the shrimp plant in India come against a broader backdrop. The same week that the whistleblower documents were published, the Corporate Accountability Lab, which is an advocacy group of lawyers and researchers, released a report detailing severe cases of captive and forced labor as well as environmental concerns often tied to wastewater at a variety of other shrimp plants in India.

After leaving his job at Choice Canning, Farinella returned to the U.S. and filed whistleblower complaints to several federal agencies. These complaints also allege a variety of food safety violations, including that the company knowingly and illegally exported shrimp that had tested positive for antibiotics to major American brands in violation of federal law.